We take so much for granted these days, including the characters that grace T-Shirts, star in video games and earn a studio over $280 million in profits. I'm talking about Marvel Comics superheroes in particular and the weird creation of that empire that became what it is today. Back before the creation of the Fantastic Four, Stan Lee was a frustrated writer/editor, etc in charge of as dwindling line of publications for Martin Goodman.

We take so much for granted these days, including the characters that grace T-Shirts, star in video games and earn a studio over $280 million in profits. I'm talking about Marvel Comics superheroes in particular and the weird creation of that empire that became what it is today. Back before the creation of the Fantastic Four, Stan Lee was a frustrated writer/editor, etc in charge of as dwindling line of publications for Martin Goodman.

Stan was bored and hated his job. His wife talked him into to 'doing it his way' before throwing in the towel and he met up with his pal Jack Kirby, a veteran cartoonist that little Stanley Leiber used to deliver coffee to back in the day. Over a light snack and lots of coffee, they hashed out a few ideas and Jack ran home only to draft up the first issue in a flash. He apologized, but Stan just ran with it and embellished the pages with dialog, narration, etc.

The Marvel Method was born.

The Fantastic Four was a hit and Stan went on to helm Spider-Man, Iron Man, the Hulk, Dr. Strange, the X-Men, the Avengers, Giant Man and the Wasp and many more, each time giving the talented artists breakdowns and summaries to work from and develop into a finished product. There are many opinions here that the work was 50/50 and the ownership of the product should be as well. Why shouldn't Steve Ditko co-own Spider-Man? At the same time, Stan was the head of Marvel Comics, and played so many roles at once I cannot imagine anyone else doing it at all, never mind making a success of it.

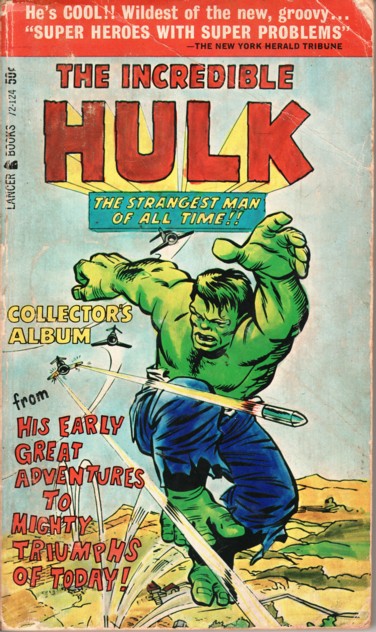

Stan also took to the road and spoke at universities across the nation about the importance of the comic book, selling paperback reproductions to the over 18 set. In later years he moved to California and became involved in what promised to be the birth of Marvel Comics Entertainment, a mega corporation extending into animation, TV and feature films. Some of these notions bore fruit while others flopped, but he was at the heart of it all.

Stan also took to the road and spoke at universities across the nation about the importance of the comic book, selling paperback reproductions to the over 18 set. In later years he moved to California and became involved in what promised to be the birth of Marvel Comics Entertainment, a mega corporation extending into animation, TV and feature films. Some of these notions bore fruit while others flopped, but he was at the heart of it all.

Regardless, these odd comic books from the 1960's, books that ran when the industry was so poor that Marvel borrowed distribution slots from their competition, DC Comics, have since become a very very big deal. They are part of the consumer pop culture lexicon. They are fast becoming the wallpaper of our culture.

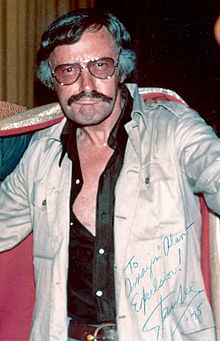

Whatever your opinion on the man, there's just no one else like Stan Lee in the industry. It's a bit disappointing that he speaks in standard speeches that make his remembrances rather suspect, but he is never boring and never fails to charm.

In recent years, a more vocal support of the creators cut out of the profits made from their creation has grown in volume. Marv Wolfman went to court over his creation Blade and lost. Gary Friedrich sued Marvel over ownership of Ghost Rider and also lost (just before the dire sequel hit theaters). Kirby was rumored to not be interested in gaining ownership of his creations and was instead keen to make new ones, but there was some bad blood between him an Lee. Ditko, the most reclusive of artists, maintained that he co-created Spider-Man yet has no interest in taking his case to court. It's a simple state of fact.

In an interview with Jonathan Ross, Lee reluctantly admitted that while Steve Ditko can say what he likes, Stan himself does not agree that it was a 50/50 split. In fact, he implies that it was HIS idea. Stan was also visibly upset that this statement came out (on camera) for obvious reasons.

89 year-old Stan Lee was interviewed with all of these details in sharp relief. The interviewer is incredibly well informed (as evidenced by the lengthy lead-in explaining the process of creating a comic book and Stan's role therein. As the Avengers gains more exposure and Marvel Comics, a company once on the brink of bankruptcy, becomes just as important to investors and the guy on the street as it has to me since I could read, it's interesting to get 'the Man's' opinion.

Officially, Lee wrote the books and Kirby drew them. Officially, Stan supplied the realism — his heroes had flaws, they argued among themselves, they were prone to colds and bouts of self-loathing, and sometimes they'd forget to pay the rent and face eviction from their futuristic high-rise HQs, which were in New York, not a made-up metropolis — while Kirby supplied the propulsion, filling the pages with visions of eternity and calamity, along with action sequences that basically invented the visual grammar of modern superhero comics.

As Marvel grew, Stan was writing more and more books for Kirby and other freelance artists to draw. Sometimes, to keep the process moving and his artists busy, he'd just supply them with a rough outline, some plot points, a few ideas for action beats; when the finished art came in, Stan would fill in the words around it, a comics-creation process that became known as the Marvel Method. And — as time went on, especially when Stan worked with Kirby — the collaboration became even more fluid. Lee and Kirby would hash out the details of a story together, kick it back and forth. Or Kirby would come back with pages that departed significantly from Stan's initial idea and then Stan would adjust his story accordingly. Different stories came together different ways, but essentially they were co-storytellers. And the work they did together during those first few years transformed the American comic-book industry and laid the groundwork for the billion-dollar trademark empire Marvel would eventually become.

The difference between Stan and Jack was that Stan, in addition to being a writer, was management. He was Marvel's editor-in-chief and de facto art director; later, he was Marvel's publisher. Finally, around the turn of the '80s, he left behind the day-to-day business of comics and moved to Los Angeles to get Marvel's movie and television division up and running. Really, though, he became what we'd now call a brand ambassador. In his comics writing — and his monthly column, Stan's Soapbox — he'd cultivated a jivey, ironic, hipster-huckster editorial voice; now he applied that voice to a new career as a professional interviewee and talk-show guest. His role at the company became more and more ceremonial. Yet the words "Stan Lee Presents" continued to appear on the title pages of Marvel comic books whose content he'd had no more to do with than Walt Disney (d. 1966) does with Hannah Montana.

The difference between Stan and Jack was that Stan, in addition to being a writer, was management. He was Marvel's editor-in-chief and de facto art director; later, he was Marvel's publisher. Finally, around the turn of the '80s, he left behind the day-to-day business of comics and moved to Los Angeles to get Marvel's movie and television division up and running. Really, though, he became what we'd now call a brand ambassador. In his comics writing — and his monthly column, Stan's Soapbox — he'd cultivated a jivey, ironic, hipster-huckster editorial voice; now he applied that voice to a new career as a professional interviewee and talk-show guest. His role at the company became more and more ceremonial. Yet the words "Stan Lee Presents" continued to appear on the title pages of Marvel comic books whose content he'd had no more to do with than Walt Disney (d. 1966) does with Hannah Montana.

Over the years, Marvel changed hands, went bankrupt, reemerged, restructured. Stan stayed in the picture. Each time he renegotiated his deal with the company, he did so from a unique position — half elder god, half mascot. Administration after administration recognized that it was in their best interests PR-wise to keep him on the payroll. For years, he received 10 percent of all revenue generated by the exploitation of his characters on TV and in movies, along with a six-figure salary. This came out in 2002, when Lee sued Marvel, claiming they'd failed to pay him his percentage of the profits from the first Spider-Man movie, a development the Comics Journal compared to Colonel Sanders suing Kentucky Fried Chicken.

It's unclear if Stan still co-owns any of Marvel's characters, but the company continues to take care of him. When Disney (which, full disclosure, is also the parent company of ESPN, which owns the website you're now reading) bought Marvel for $4 billion in 2009, part of the deal involved a Disney subsidiary buying a small piece of POW! Entertainment, a content-farm company Stan co-founded; another Disney-affiliated company currently pays POW! $1.25 million a year to loan out Stan as a consultant "on the exploitation of the assets of Marvel Entertainment."

Jack Kirby, on the other hand, was a contractor. You could sink a continent in the amount of ink that's been spilled on the question of whether it was Stan's voice or Jack's visuals that ultimately made Marvel what it was, but it's hard to argue that any of this would have happened had Kirby been hit by a bus in 1960. Yet like most comics creators back then, he was paid by the page and retained no rights to any of the work he did for the company or the characters he helped create; by cashing his paychecks, he signed those rights over to the company. It took him decades just to persuade Marvel to give him back some of his original art, much of which was lost or given away or stolen in the meantime; there are horror stories about original Kirby pages being gifted to the water-delivery guy.

Jack Kirby, on the other hand, was a contractor. You could sink a continent in the amount of ink that's been spilled on the question of whether it was Stan's voice or Jack's visuals that ultimately made Marvel what it was, but it's hard to argue that any of this would have happened had Kirby been hit by a bus in 1960. Yet like most comics creators back then, he was paid by the page and retained no rights to any of the work he did for the company or the characters he helped create; by cashing his paychecks, he signed those rights over to the company. It took him decades just to persuade Marvel to give him back some of his original art, much of which was lost or given away or stolen in the meantime; there are horror stories about original Kirby pages being gifted to the water-delivery guy.

Kirby never sued Marvel, over the art or anything else. But as the years wore on he blasted the company in interviews. He blasted Lee, its avatar. Compared him to Sammy Glick. Referred to him as a mere "office worker" who'd grabbed credit from true idea men. "It wasn't possible for a man like Stan Lee to come up with new things — or old things, for that matter," Kirby told the Comics Journal in an infamous 1990 interview. "Stan Lee wasn't a guy that read or that told stories. Stan Lee was a guy that knew where the papers were or who was coming to visit that day."

-----------------

I ask him if he feels, in general, that the comic-book industry has been fair to comic-book creators.

"I don't know," Stan says. "I haven't had reason to think about it that much." Five-second pause. "I think, if somebody creates something, and it becomes highly successful, whoever is reaping the rewards should let the person [who] created it share in it, certainly. But so much of it is — it goes beyond creating. A lot of people put something together, and nobody really knows who created it, they're just working on it, y'know? But little by little, the artists and the writers now are a different breed than they were, and most of them, if they create anything new, they insist that they be part owners of it. Because they know what happened to Siegel and Shuster, and to me, and to people like that. I don't think it's a problem anymore. They make much more money than they used to make, when I was there. Proportionately.

"Everybody thought that I was the only one that was getting paid off, but I never received any royalties from the characters. I made a good living, because I was the editor, the art director, and the head writer. So I got a nice salary. That was all I got. I was a salaried guy. But it was a good salary. And I was happy."

Read the entire fantastic article here.

From the outside this may look cut and dry as to who owns what and who is due what, but to actually read the books you can clearly sense both Stan's voice as an author and the dividing lines between script and art. Ditko's contribution to Spider-Man is plainly evident, yet you can also see a part of Peter Parker still living in Stan Lee beneath those thick tinted glasses.

Regarding the way creators have been treated by the corporation that Marvel has become, I am reminded of the pride with which Gary Friedrich spoke to me about Ghost Rider at a comic book convention, his humble wares on the table for sale. He was later fined an absurd sum of $17,000 for profits that he made from Marvel's character. There's an argument that Ghost Rider may have been the creation of one or two people, but it was printed and distributed by a company. The quality of the product combined with the efforts of the publisher made it a success... so why would anyone want to shaft a writer by not only denying him his claim but also asking for recompense when it is clearly not needed?

Stan Lee skirts over this issue in the interview above and for good reason. He had received a lump sum payment of $1 million-a-year for a time (and may continue to do so) for his efforts. Herculean though they are... he may want to spread the good fortune to others who also deserve some recognition. At least a cup of coffee and a ticket to the premiere.

It's strange when an idea in becomes something on paper, then something mass produced... turned into a copyrighted image to be used on anything from toys to headphones or toilet paper. I can't help but feel understanding and frustration for the creators as their work becomes some abstraction that has grown out of their control.

Note: Current Marvel Comics COO Joe Quesada is a member of Hero Initiative, an organization that provides assistance to comic book professionals. He became personally involved in helping Gary Friedrich when he learned of the court ruling.